|

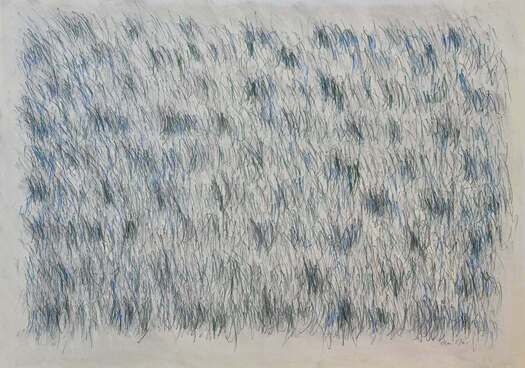

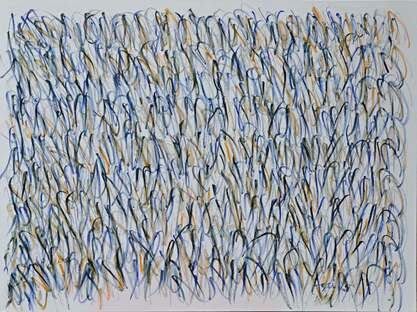

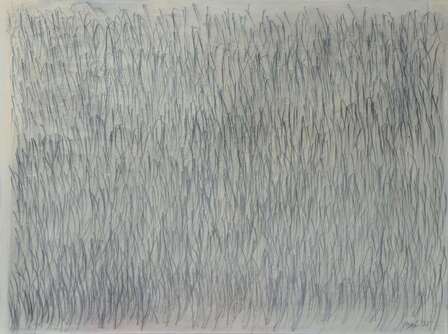

I recently sold a painting – Harvested Rice Field in Snow – and have been thinking about where this painting came from. It’s not something I’d ever thought through. It’s only now that I realise that it took three years for this painting – these marks – to evolve. Between February 2020 and the end of 2022, the experience of walking past harvested rice fields in winter in Northern Japan sunk into me, sunk below a conscious remembering. Let me explain what I mean. In February 2020, my husband, Toshi, and I visited Akita prefecture in North Western Japan, the home of the famous Akita dog. One day we walked through a snow-covered landscape of harvested rice fields and took some photos. I’ve always loved the aesthetics of a harvested field. A harvested field is a scratchy mark on a flat surface. I’m not interested in representing the lines in the field with two-point perspective – like a fence or train tracks or telegraph poles receding into the distance to a single point. I don’t even notice perspective in this way. To my eye (and mind), a field is flat. It is, actually, a big, flat square. The lines are parallel. That is what I know. That is what I feel. That is what I draw. A canvas is flat too. Let’s not pretend that it isn’t. To be honest, for me, perspective is a lie. And the marks? For some reason, I love scratchy marks. There’s something satisfying about applying a sharp implement to a hard surface – the feel of it, the sound of it, the experience of it – scritch, scratch. So almost two years after I saw these fields, at the end of 2021, I did some drawings. The first was quite photographic. It wasn’t satisfying, so I did another. It was better, but somehow it wasn’t right, but I was stuck, so I abandoned the idea. I forgot about it. In the second half of this year – 2022 – I started making a work on canvas, where I scratched regular marks into thick, white, oil paint with an etching tool I’ve had since my first year at art school in 1981. It’s a familiar friend. I completed the painting in one hit – in one breath – while the paint was still all of the same sticky consistency. I was happy at the end. It just seemed right. Where did it come from? What was it about? I didn’t know. It felt whole, complete and alive. That was enough. When I decided to display the finished work a few weeks ago, it needed a title. It was only then that I realised what I’d made – a harvested rice field in a snowy landscape. The idea I’d forgotten a year before, perhaps because I had ‘forgotten’ it, had emerged as something new and complete. Not a pale, representational reflection of something else in the world, but something original; and also something that contains all the ideas about painting, abstraction, and the gesture, that I have talked about here and in my previous post. As such, Harvested Rice Field in Snow is both a distillation and a single, complete, original thing. It is art. Thank you for reading.

0 Comments

We’ve all heard the clichés - “That’s not art.” “My pre-schooler could do that.” A visitor to one of my exhibitions once said to me – “Why can’t you paint something I can understand?” I suspect that this person was referring to an image-based visual language. Our world, our culture, is flooded with image-based art. We all understand these images. We can ‘read’ this ‘language.’ Perhaps you sometimes feel confused when you see non-representational artwork, just like my outspoken gallery visitor. Perhaps you wonder if it may be a case of ‘the emperor’s new clothes’. Or perhaps you can appreciate the colours and patterns, but wonder if it’s just that – beautiful marks, colours and patterns but rather superficial. Does the work have any other meaning? Where do marks come from? Are they saying something? Or nothing? Are they just a doodle or a scribble – meaningless and somewhat childish? I can’t speak for all abstract art, but in this post, I’d like to explain why my way of working has become an exploration of mark making in an abstract and semi-abstract gestural style. “Any mind worth calling a mind must have needs beyond the existing categories of language.” Ezra Pound 1885-1972 We know that a single verbal language cannot express all meanings. There are words in foreign languages that express ideas not expressible in our native language. In the same way, abstract art ‘articulates’ in a visual way, ideas, memories, thoughts and emotions that representational art cannot. Artists create new ‘languages’ when existing languages become inadequate. This is where originality comes from. Artists don’t create something new for the sake of it. They do it because the tools they are given are not commensurate with their experience. They must create something new in order to explore and understand themselves and share their humanity with others. The language I often use, of the abstract, gestural mark, is not a representational, image-based language. It is a language of the heart and of the sub-conscious. A language of emotion and unarticulated memory. Perhaps it is prescient too, revealing something about the world that is not yet obvious – that is still only a vibration. My gestural style is also grounded in the idea of recording my presence in the moment – in the moment of creation. I’m fascinated by the process of how my hand, via my eye, breath, the pulsing of my heart – this physical body – connects to something often semi-conscious – to create marks on a surface. Like a seismograph recording how the world registers upon me. The hand, the eye, the heart, the mind, now, in this moment, registering presence. In isolation, this doesn’t always reveal meaning, or tell a story, just as a single letter or word is not a language. But over time, and as a part of a larger body of work, all these paintings and drawings are telling the visual story of my life, at an almost cellular level perhaps, within the world in which we all live now. I hope this goes some way to explaining why I work the way I work. I hope it helps you to become more curious, not only about my work, but about art in general and about abstract art in particular. And if you’d like to read a story about where some of my marks come from, read on to my next post – The Evolution of a Mark. Thank you for reading. Have you ever noticed an embossed symbol at the bottom of an artist’s print? Maybe you’ve seen little red stamps on old Chinese or Japanese artwork? These are called chops in English. The word comes from the Hindi word chaap, meaning stamp, imprint, seal or brand, or instrument for stamping. It entered English via India in the early 19th century, referring to a trademark. Stamps and seals have been used for millennia as a mark of authenticity. In Japan today, these signature stamps, called Hanko, are more important than a personal signature, and are used for banking, signing contracts and official documents, and even receiving parcels. Chops, which can be made from clay, wood, rubber, or linoleum, are usually relief printing blocks, pressed into ink and stamped onto the surface of the paper. Traditionally, they use indelible red ink, and on art works the mark frequently forms part of the design, as well as being a signature. It is a tradition in Western printmaking for blind embossed stamps, also called chop marks, to be used as a sign of authenticity and quality. Blind stamping means embossing paper, without ink, using a unique stamp with a special press. It is very difficult to forge a blind stamp, as it becomes an integral part of the paper and the art work and cannot be removed. The fine art print trade is obviously very concerned to ensure authenticity, and many print studios have their own unique blind stamp to emboss their prints and give them provenance. Also, if the artist hasn’t signed the print, the stamp proves that it is genuine. These stamps can also be added to original prints by the artist, or by a collector. Galleries who manage an artist’s estate have chops made for that artist to authenticate the prints of their work. So what has this to do with me? Well, I have started having fine art prints made of my work by Printroom Editions, a highly professional and experienced studio specialising in the printing of original art work. On their recommendation, I have had my own chop made. As well as signing and numbering my prints, I am also having them blind embossed, with my own ‘signature’ chop. It looks beautiful when it is embossed onto the print. The white-on-white mark sits quietly in the bottom left-hand corner of the heavy printing paper. I love running my fingers over it. Embossing is really more of a tactile experience than a visual one, don’t you think? The design of my stamp is inspired by the Japanese enso. Also known as the Zen circle or infinity circle, it is one of the richest symbols of Zen Buddhism and one of the most common subjects of Japanese calligraphy. Using a bamboo brush and ink, it is traditionally drawn using only one, swift, continuous brushstroke as a meditative practice for letting go of the mind and allowing the body to create. It is a manifestation of the artist, and their context, at the moment of creation – breath, hand, body, and mind – in the world, in that moment. In Zen philosophy, it is the revelation of a world of the spirit without beginning or end, reflecting the transforming experience of enlightenment - perfectly empty yet completely full. An enso may be open or closed. The closed circle can, among many things, mean the totality of the experience of life, and the cycle of birth and death that continues endlessly. The incomplete circle allows for movement and development, as well as representing an acceptance of the imperfection of all things. I have chosen an incomplete enso for my chop, to express the sense of my creative life as something that is always becoming through an exploration of the beauty and wonder of imperfection within each moment. Thank you for reading. |

Pamela AsaiVisual artist and poet living and working in Brisbane, Australia. ArchivesCategories |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed